In previous posts, we learned how river cruising evolved from an experimental steamboat on the Saône to paddle-wheelers plying rivers in the United States and Europe. These evolutions, however, were only beginning to resemble river cruising as we know it today. In the 1960s, vessels were being built to carry passengers on overnight voyages along the rivers. In this post, we’re going to visit one such vessel, not on a river but on a canal in France.

It’s hard to imagine, but the beautiful hotel barges that putter along the European canals today had their beginnings in carrying coal and other cargo. Sooty and dirty, these flat bottom boats were the workhorses of transport, and in fact, these motor-less vessels often were pulled by horses, mules and even people along towpaths flanking the waterways. As we’ll discover, in the 1960s a few of these barges were converted to carry people, a transformation that would change the course of tourism for those visiting Europe.

Modern hotel barges, like the one in the photo above, ply the waterways of France primarily. Today, nearly all hotel barges feature compact but functional staterooms with private bathrooms, cozy lounges where beverages are included in the fare, restaurants where solo chefs serve up sumptuous fare, and all the luxuries of boutique hotels. Hotel barges offer some of the most exquisite holiday options in Europe, which is why I chose to host annual barge trips (the year 2020 being an exception) on the French canals.

In this post, we’ll learn how a young Englishman introduced a new holiday concept by converting a 40-year-old cargo barge from carrying coal to carrying guests, and how a best-selling American author helped trumpet the young man’s new way of vacationing to the masses.

A man and woman pull a barge along a towpath in the Netherlands,1931. Photo courtesy Dutch Nationaal Archief., Wikimedia Commons

Hotel Barges Vs. Riverboats

Before we discuss how hotel barges evolved, it may help to know exactly what they are and how they differ from the river cruise boats. First, there’s the size factor. Hotel barges are smaller and have fewer frills and amenities than river cruise boats. The size difference can be best envisioned in passengers. Whereas river boats usually carry more than 100 passengers, barges range from a few passengers to a couple of dozen at most.

Another big difference between a river cruise and a barge adventure is the amount of territory you’re able to cover. Barge trips usually span six days and travel fewer than 50 miles of canals, while river cruisers may travel a few hundred miles on rivers. And while barges transit canals (with some exceptions), river boats transit rivers.

On both barges and river boats, transiting locks is frequent, but on barges guests are able to get off at a lock to walk or cycle along the old towpaths, joining the barge at lock further along the canal. If you did that on a river boat, you’ll likely not see the boat again.

A barge normally cruises within one region of one country while a river boat can travel through several countries and on several rivers during the span of one sailing. Although barge cruises are offered in the United Kingdom, Belgium, Germany and Holland, the majority of hotel barges operate on the vast network of canals that run throughout France.

Barges typically have only two decks, smaller staterooms when compared to river boats, and a smaller dining room and lounge. Barge staterooms almost always have private en-suite facilities, but there are exceptions. Barge adventures are usually all-inclusive, including drinks, fine wine and champagne; gourmet cuisine (using fresh, local ingredients – sometimes shopped from markets along the canals and cooked to order). Excursions also are included, and bicycles are often available for use along the towpaths that run alongside many canals. Some barges even have whirlpool tubs, perfect for a soothing soak while puttering past beautiful landscapes.

Barges will appeal primarily to those who want to explore the French countryside on slow-moving vessels with small groups of like-minded people. River cruises will appeal to those who want to explore Europe’s storied rivers and their marquee cities on vessels with larger staterooms, multiple dining venues and more amenities than they’d find on barges.

Both river cruises and barge adventures are ideal ways to explore inland Europe. For those who have river cruised the European rivers, barge adventures are the next logical step, moving from larger vessels to smaller ones. For small groups also, barge cruises are good options to share intimate experiences with like-minded friends and family.

The Conversion: From Carrying Coal To Carrying People

Still in operation today, the Luciole was constructed in 1926 as the mule-drawn vessel Ponctuel (later equipped with an engine). In 1966 an Englishman, Richard Parsons, bought Ponctuel and converted it to become the first hotel-barge plying the rivers and canals of France. Parsons renamed the barge Palinurus. Capable of carrying 22 passengers, Palinurus operated in the Burgundy region and continues to operate today. Photo: HectorDavie, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Now that we understand the nature of hotel barges, let’s look at how they evolved. Barges date from the 18th century, when, during the Industrial Revolution, Great Britain developed a network of narrow barges to transport cargo. By narrow, we mean no more than seven-feet wide to accommodate the canal locks.

Locks, by the way, are constructions along rivers and canals to accommodate transit in differing water levels. The locks operate by gates that close at either end so that the lock can fill with – or empty itself of – water to raise or lower boats. Think of locks as steps that allow boats to climb up or down.

Throughout Europe, barges carried bulk and other cargo that was difficult to ship by traditional land-based methods, and even after the adoption of the railroad as a method of moving goods and passengers, barging remained an economical and popular way to conduct business. Railroads were limited by their fledgling infrastructure. Fluctuations in the gauge, or track size, used between competing companies often meant that trains could travel no farther than a country’s geographical boundaries.

As rail transport improved and became standardized, more and more goods began to be shipped via train instead of by barge. The introduction of delivery trucks and other automobiles in the early 1900s meant that goods could be driven locally between two points, causing a further reduction in the amount of cargo shipped by barge along Europe’s waterways. In the 1960s, the decline in goods shipped over the waterways of Europe caused one enterprising young man to come up with a radical idea: He would convert a barge from carrying cargo to carrying passengers in order to ferry people on long pleasure cruises up and down the French canals.

A young newspaper reporter for Reuters, Richard Parsons was an enthusiast for the English canals, says his friend and fellow canal enthusiast John Liley, author of France – The Quiet Way. “While we knew our home waterways intimately, with their seven-foot-wide locks in a quirky, wriggling network, we knew little of France,” Liley says. “But Richard plunged in.”

Still in his early twenties, Parsons purchased a 40-year-old retired barge known as Ponctuel (French for punctual), which had once been pulled along the waterways by mules. In 1966, Parsons and his brother repositioned the 30-meter (98 feet) vessel to Dunkirk and refitted it into the first hotel barge on the French canal system.

Parsons named his new barge for the helmsman of Aeneas’s ship in Roman mythology, Palinurus. The name implied that the barge was a navigator or guide for adventures on the waterways. He explains on a blog that he still maintains that though it is considered to be bad luck to the change the name of a boat, he did not want to operate a barge called punctual. “I didn’t want to be on time,” Parsons writes, “so we had to look for another name.” As he discovered later, however, it was important to be punctual for the locks, which operated on a rigid schedule.

After refitting and renaming the barge, Parsons charted a course on the canals of Burgundy. “Once started, he faced all manner of difficulties from French licensing authorities and tax people, none of whom had dealt with such a business before,” Liley told me. “But the biggest problem of all lay in finding the customers.”

There were other challenges in those early days as well. The waterways still catered primarily to cargo traffic, so it wasn’t uncommon to be stuck at the back of an extremely long queue of freighters waiting for their turns in one of the many locks along France’s waterways. Other areas had almost no traffic at all and as a result overgrowth from surrounding trees nearly blocked access to locks and waterways. The experience, on the whole, was an uneven one, only suitable for the adventure traveler who didn’t mind a few bumps along the road.

A Beautiful ‘Floating Island’

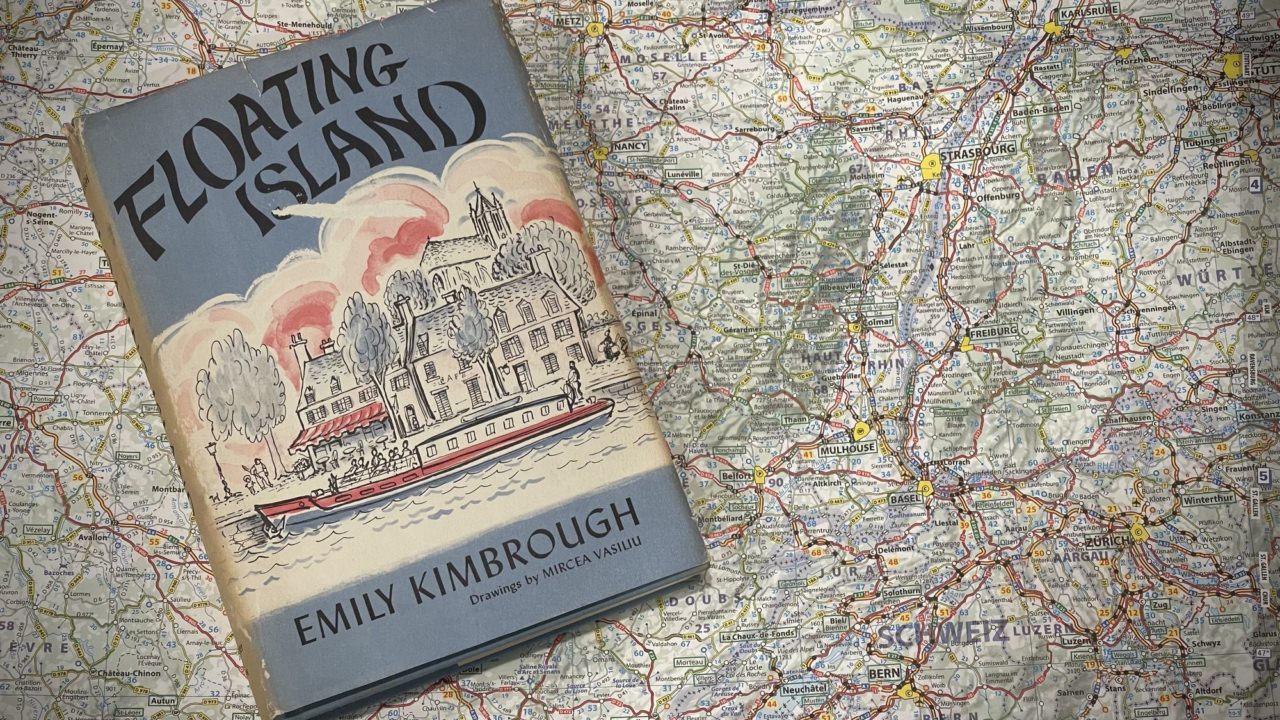

In his second year of operation, Parsons had the good fortune to attract a party led by Emily Kimbrough, a best-selling travel writer whose book “Floating Island” would transform Parsons’ business and subsequently modern-day river cruising.

Unwittingly, writers played a major role in river cruising’s success. Emily Kimbrough’s 1968-book Floating Island, for example, introduced a new style of travel through France – on barges transiting the canals. When Kimbrough was born in 1899, there was no river cruising as we know it today, and in fact, would not be for the majority of her life. Through her affectionate account on a newly converted barge, she would play an instrumental role in changing that. The multi-day barge journeys were the predecessor to larger vessels that ply the European rivers today. © 2021 Ralph Grizzle

Kimbrough chartered Palinurus. In her book, she wrote that it wasn’t difficult to convince her friends to join her on a barge adventure. “I have never sold Fuller brushes nor Avon beauty products,” Kimbrough wrote, “but I sold places on the Palinurus so rapidly the passenger list opened and closed on the same day.”

Among those who would travel with her: actors and actresses, playwrights and authors, her bother and sister-in-law, a surgeon and teacher, a retired Rear Admiral (who was pleased by the prospect of a barge as it would be a good change from big ships), and a civil rights activist. Altogether, 11 people, a mix of couples and singles, signed on. .

Their reasons for wanting to go: Some, because it was France; some wanted to learn French, others wanted only to hear French spoken. One wanted only to “move slowly along the waterways – no high seas, not even waves ‘ through beautiful country in the spring.” One couple, playwrights, loved travel but were sold when they learned there would be bicycles on board so that they could cycle on the towpaths that lined the canal.

After boarding Palinurus, Kimbrough wrote of a 1958 canal cruise in England and Wales: “Compared with what I had experienced on the English canals, where we had occupied cells and slept on the equivalent of ironing boards, these cabins seemed equivalent to accommodations on the Queen Elizabeth.” Remember, Britain’s locks at that time limited the width of boats to seven feet, so you can imagine how cramped the accommodations must have been.

Palinurus was far from palatial. The 22-guest vessel was equipped with bunk beds and two toilet facilities at each end of the central passageway. But the experience struck a poetic chord for Kimbrough.

”From their lively explorations on land, the passengers returned to the dreamlike rhythm of the barge, a veritable floating island, content to be released from the tensions ashore, detached from earth and time.” – Floating Island, Emily Kimbrough, Harper & Row, 1968

Nearly 70 at the time, Kimbrough published her book in 1968, piquing the interest of the American public. Floating Island brought American travelers to France to experience barging for themselves. In an age where the internet and other forms of “instant” communication simply did not exist, barging owed its success largely to word-of-mouth. Small groups of friends would often charter a barge for a trip through France, returning to tell friends, family and co-workers about their experiences. Some of these acquaintances would become more intrigued and eventually book passage for themselves.

The influx of North Americans was largely responsible for the race to outfit ships with better and more luxurious accommodations. What began as a fun diversion by a dedicated entrepreneur had suddenly blossomed into an industry that was in high demand.

Parsons acquired other barges. Increasingly, the new barges featured en-suite bathroom facilities, which were critical for the success of barge and river cruising. Palinurus transferred from Burgundy to the Canal du Midi in the south of France.

Parsons didn’t really think much of the invention at the time, stating in a 2008 interview with France Today: “We never thought about luxury then—it was just the idea of a fun holiday, walking and biking and eating and drinking. The most exciting thing for me was that no one else was doing it.”

John Liley, mentioned earlier, purchased Palinurus in 1985, bringing her back to Burgundy, modernizing the cabins, raising the lounge roof and, in general, changing so much it is hard to find, internally, much that is original. His children still operate the barge, now renamed Luciole (Firefly). Luciole cruises the Canal du Nivernais, “the very best waterway, in my observation, on the French waterway system,” Liley says. Luciole carries 12 guests in eight en-suite cabins, with no single supplements. If you’d like to learn more about Luciole, visit www.bargeluciole.com.

Parsons remains a family friend. Penny Liley, who runs the day-to-day operations, told me: “The biggest compliment he gave me was by saying that the Luciole still cruises with the same spirit as when she was the Palinurus.”

Today Palinurus still operates, though much improved, as Luciole. Photo courtesy of Hotel barge Luciole

In attempts to lure even more travelers from North America, barges began to be acquired and refitted at a rapid rate. As competition on the waterways grew for this new lucrative passenger traffic, owners and operators began to think more creatively in terms of both interior fittings and itineraries. Gone were the days of shared bathroom and washroom facilities, replaced instead with staterooms that more closely resembled the finest luxury passenger liners of the day. Exquisite woodworking and lounges that recalled the interiors of the Grand Salons of Paris or the extravagance of the Orient Express instilled these barges with distinctive charm that replaced a once utilitarian persona.

As airline travel became more affordable to the masses, the time and expense required to cross the Atlantic by ship, then embark on a multi-week barging experience was mitigated. Between the late 1960s and the 1990s, a handful of new river cruise operators attempted to capitalize on the trend of touring Europe by boat. Barges began to give way to what was beginning to look like the river cruise ships of today. The river boats could be no larger than the locks along the rivers, up to about 440 feet long and 38 feet wide. As you’ll learn later, there have been exceptions to the ship’s width.

In our next post, we’ll learn about the early pioneers who launched the river cruise brands that still operate today. Their trials and triumphs illustrate that river cruising was not an overnight success. Many of the early river cruise boats drew heavily on their predecessors for influence, taking the no-frills barging experience and placing it on a newer ship capable of holding more paying passengers. Before going further, however, we’ll need to wind back the clock once again and go to place not often associated with canal cruising. Next, we head to Stockholm, Sweden to board the world’s oldest registered cruise ship.

In this 2016 photo: Pictured with their sons, Richard Parsons, who began hotel barging with Palinurus in 1966 (second from left) and John Liley, who purchased Palinurus in 1985 and continues to operate it, now known as Luciole.

The Role Of Writers

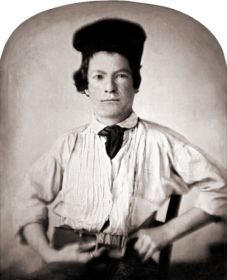

Samuel Clemens at age 15. Clemens later adopted the pen name Mark Twain, publishing Life On The Mississippi in 1883. Photo Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Barges were responsible for river cruising as we know it today, but there was one other component: literature. Though seldom credited with river cruising success, literature has played a critical role in inspiring aspirational trips on rivers worldwide. The poet Heinrich Heine popularized the landmark Lorelei, a highlight on Rhine River cruises today that tourists throng to see. Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi inspired millions to cruise – or want to cruise – the Mississippi. In her book Floating Island, Emily Kimbrough brought French canal trips on barges to the minds of the traveling public.

All three of these writers played a role in the popularity of river cruising today. They were the early marketing mavens, although their intent was likely rooted in producing literature. The tradition continues today. Our site, for example, continues to use writers to convey the experience of river cruising. River Cruise Advisor’s mission, in fact, is the provide readers with resources that empower them to make informed decisions about their cruise vacations. Some of our most popular content mirrors what Emily Kimbrough produced in Floating Island, travelogues that describe the experience of being in Europe on a river boat or barge.

Also see 10 Reasons To Choose Barge Cruising

Leave a Reply