Today marked a full day of touring the capital of Cambodia for guests aboard AmaWaterways’ AmaLotus. Phnom Penh is an exciting mix of old and new. There are trendy bars and restaurants that line the River Walk waterfront, while just a few blocks in, barbers provide haircuts and straight-razor shaves in chairs on sidewalks.

In recent weeks, several high-profile protests at Wat Phnom — just a few blocks away from where AmaLotus berthed — resulted in some changes to our excursions. Although these protests had largely subsided, guests were encouraged to stay onboard the ship and not venture out beyond 10 p.m., which was disappointing but understandable given the current climate.

Our full day of excursions — all of which are included in the cost of the cruise — took us to see the Royal Palace and the National Museum of Cambodia.

The Royal Palace is startlingly elaborate, with floors constructed of silver tiles weighing one kilogram each that were imported from China. Chandeliers adorn the building interiors, and picturesque gardens filled with lotus flowers cover the grounds.

At the National Museum of Cambodia, artifacts from the country’s past are on display for all to see, many of which would have been either lost or destroyed had they not been protected. There are artifacts here that pre-date Angkor Wat.

But as enjoyable as it was to see these sights, our tours this afternoon to the Killing Fields and the S-21 Detention Centre are likely to be what will remain with guests. Those tours were powerful — and essential to any visit to Phnom Penh.

Today’s tours highlighted the reign of the Khmer Rouge. It’s a disturbing subject that affected me profoundly.

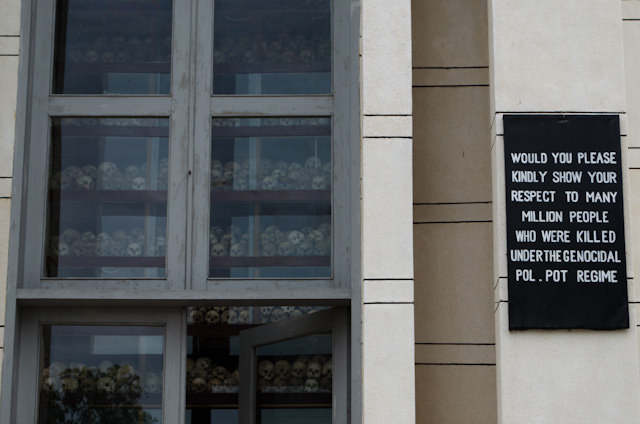

Our first stop in the afternoon was the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center, perhaps better known as one of the more than 300 killing fields used during the reign of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Located approximately 9 miles (15 kilometers) southeast of Phnom Penh, the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center is anchored by a massive memorial Stupa that contains the skulls of hundreds of victims.

The most interesting thing about this particular killing field is that it isn’t the sprawling, open space you might imagine. Instead, it resembles a peaceful city park of modest size; simply walking around the perimeter trails would take only 30 minutes or so. Most of the original infrastructure constructed by the Khmer Rouge has disappeared, leaving only wooden placards to relate the story of what occurred here.

All around, dozens of excavated pits pock-mark the landscape. One of these was a mass grave that held 450 victims in an impossibly small footprint.

A large, majestic tree near the center of the field was known as “The Magic Tree.” It was called that because the Khmer Rouge ran a loudspeaker up the tree. Suspended in its branches, it cranked out music full-blast in an attempt to drown out the anguished cries of the people being murdered below. It ensured that neighboring residents never heard the screams — only the music.

A dozen feet away is the barren trunk of a tree where children were brutally beaten. The Khmer Rouge had a method for disposing of those who came to Choeung Ek: the men were killed first, then the children. The last to die were the women. This order was to prevent the men from trying to save the women and children. Sadistically, the children were killed first as a form of further torture for the women who remained.

Three times a month, trucks carrying 30 terrified prisoners would show up, usually under the cover of darkness. Prisoners were immediately sent to the killing fields to be disposed. So rapidly was the Khmer Rouge working on exterminating intellectuals and foreigners (French, British, American and Australian citizens were dispatched here), that temporary staging areas had to be erected to deal with the crush of people. Since I wear eyeglasses to see, I would have been singled out for death. Having sex, practicing religion or using utensils other than spoons were also grounds for execution.

The exact number of the dead — or who they were — is not known.

The scale of human tragedy that occurred here is difficult to comprehend. It’s oddly peaceful and still here today, yet it is a place where heinous crimes occurred — now a quiet memorial to the victims. During my visit, people lit incense and placed bundles of flowers to pay respect to the dead housed within the stupa.

Our next stop on this day could never be described as peaceful or serene.

The Tuol Sleng S-21 Detention Center in central Phnom Penh has been described as being “grim.” Before coming here, I’d read about it. I knew what was going to be here, and I had an understanding of what transpired behind these walls.

Reality, however, is so much worse than “grim.” Tuol Sleng is the physical embodiment of pure hell.

Up until 1975, Tuol Sleng was the Tuol Svay Prey High School, a collection of four, three-story buildings arranged in a U-shape. But during the brutal reign of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, the high school was turned into one of more than 150 execution centers within the country.

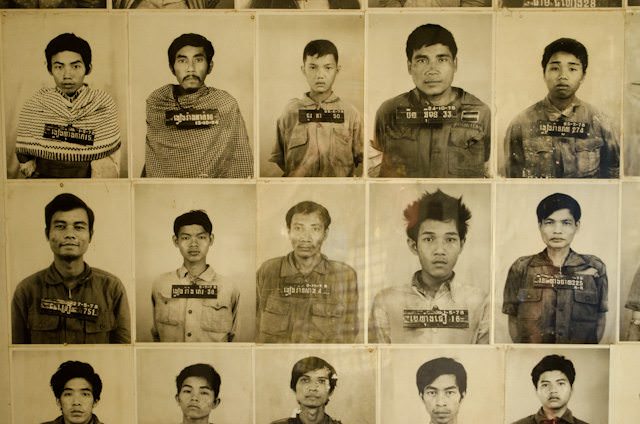

Up to 20,000 people are estimated to have been brutally tortured and killed here. Only 12 people are thought to have escaped the prison alive. Only three of those 12 are alive today. You can read about one of those who escaped in Ralph Grizzle’s story about his visit to Tuol Sleng.

The man in charge of overseeing this unbridled hatred was Khang Khek lew, a former mathematics teacher better known to his captors as Comrade Duch. He would have prisoners repeatedly and viciously tortured in order to provide names of family, friends and other potential “co-conspirators” for crimes both real and imagined. He also kept extensive documentation during his tenure at S-21, noting on one list of 17 prisoners — mainly women and children – the order for guards to “smash them to pieces.”

After the collapse of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, Khang Khek lew remained in hiding until 1999 when he was tracked down by photo-journalist Nic Dunlop. In 2007, Duch was formally charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity and detained by Cambodia’s United Nations-backed Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. He confessed: “I am solely and individually responsible for the loss of at least 12,380 lives.” He was later sentenced to life in prison, with “no chance of parole.”

The S-21 buildings have been left largely as they were when they were abandoned in 1979 by the fleeing Khmer Rouge. Our tour started at “Building A,” where Vietnamese photo-journalist Ho Van Tay found the last victims.

“Building A” consists of large rooms that have only a single steel bedframe, accompanied by some metal instruments of torture. In the first room, there was a pillow with bullet holes, its fabric grotesquely stained. The standard school-issue orange checkered tile floors were still discolored with blood. I snapped a wide-angle photograph from the entryway, then walked into the room to take another photo.

I turned around to leave and came face-to-face with something so horrifying that it sucked the breath from my lungs.

A black-and-white photograph on the wall showed the almost unrecognizable remains of a man, bloodied and shackled to the same bedframe, in the very same room where I stood. Blood leaked from the frame like a car might leak oil or coolant. The photograph was made all the more frightening by its nearly complete lack of detail of the human being stretched across the bedframe – but the pillow is there, along with the steel bar that now rests across the bed. The floor beneath my feet was still stained. Panic rolled up from beneath me in a way that I’ve never felt before.

In each room, a different bed. A different victim. A different photograph of how the room was found in January of 1979. One still features a vibrant green chalkboard, a hold-over from happier times.

To pass through these four buildings, with their formerly electrified barbed wire enclosures and hastily arranged brick cells barely bigger than a shower stall, is to descend into your darkest fears. It’s the kind of thing you’re sure can’t happen to you; the sort of terror normally reserved for slasher movies like Hostel.

Yet, for 20,000 people, this unimaginable nightmare became reality.

And then we were out; back on the motorcoach, passing Cambodians that would wave at us as we passed. Shop-keepers plied their trades and scooters zipped in and out of traffic. Thirty-four years have passed. The city has rebuilt, but its past not forgotten.

The bright lights of the AmaLotus welcomed us back onboard. We had another refreshing drink waiting for us, and cold towels were again handed out to cool us down.

As difficult as today was, I think every visitor to Phnom Penh needs to see these sites, and I am glad that AmaWaterways includes them on this itinerary. If you don’t educate the world about the past, how can we prevent it from happening in the future?

Finally, I want to say some words about the Cambodia of today, as we prepare to sail to Vietnam. I love this country; honestly, truly love it. The people are spectacularly nice and kind, and while the country is still poor and rural for the most part, the rich history the Cambodian people have is another sort of wealth.

It is also a developing country, but one that continues to attract tourists. It is a country that is managing to rebuild itself after having a third of its population exterminated just 30 years ago.

This time last week, I had no idea what to expect from Cambodia. Now, my strongest overriding desire is to plan my return.

Our Live from the River journey through Cambodia and Vietnam aboard AmaWaterways AmaLotus will continue tomorrow with a day of scenic cruising down the Mekong.

Leave a Reply